Peer Review of Manuscripts

Peer Review of Manuscripts

Latha Chandran & Virginia Niebuhr

A module designed to help you improve your skills for peer reviewing manuscripts submitted for publication.

Publication is an essential way to make one's work a genuine scholarly contribution. Publication allows for dissemination to, and potential use by, a wide audience. For work to be published in scholarly journals, it must pass the peer review process.

Learning to peer review can be important to academicians for several reasons. First, as an academic scholar, it is important to volunteer as a peer reviewer to contribute your own expertise to your profession. Reviewing is an activity which can add to your credentials as a scholar. Second, you are more likely to have your own work published if you understand the review process. Third, learning the methods of peer review will make you a better writer.

This module is designed to help you improve your skills for peer reviewing manuscripts submitted for publication.

With permission from the publisher of Academic Medicine, this module was built around the CHECKLIST OF REVIEW CRITERIA FOR RESEARCH MANUSCRIPTS. The CHECKLIST was prepared by a Joint Task Force from Academic Medicine and the Group of Educational Affairs of the Association of American Medical Colleges, and published in a monograph series in Academic Medicine in 2001.

Monograph Series: Bordage G, Caelleigh AS, Steinecke A, Bland CJ, Crandall SJ, McGaghie WC, Pangaro LN, Penn G, Regehr G, Shea JA.

Review Criteria for Research Manuscripts. Academic Medicine. 76(9), September 2001. pp 900-975.

Checklist of Review Criteria for Research Manuscripts. Academic Medicine. September 2001, 76 (9), pp 920-921.

|

The entire list of 77 review criteria is included at the end of the module. |

After completing this module, the participant should be able to:

Peer review began as a source of advice to the editor and emerged as the gold standard for a journal to be accepted into Index Medicus. In 1978, a group of biomedical journal editors convened in Vancouver, British Columbia to discuss common problems with journal editing. The Vancouver Group evolved to the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE). The ICMJE created and now maintains the Uniform Requirements for Manuscripts (abbreviated URM, or commonly referred to as Uniform Requirements)1. The Uniform Requirements is a set of guidelines produced for standardizing the ethics, preparation and formatting of manuscripts submitted for publication by biomedical journals. Compliance with the Uniform Requirements is required by most leading biomedical journals, and over 629 journals internationally follow the Uniform Requirements.

The Uniform Requirements detail principles regarding authorship, conflicts of interest, protection of human subjects and animals in research, publishing and editorial issues such as publication of negative studies and registration of clinical trials. The section perhaps of most interest to the early reviewer is that on preparing a manuscript for submission to biomedical journals. The IMRAD format for articles (Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion) follows the logical process of scientific discovery by beginning with a gap in the existing knowledge, generating a hypothesis and developing a method to test the hypothesis, analyzing the results and discussing how it contributes to the knowledge in that field.

Specific reporting guidelines for study designs, uniform disclosure form for disclosure of conflict of interest, as well as specific instructions on the construction of individual sections of a manuscript are clearly provided in the URM. As an example, these guidelines provide specifics on what must be included in the methods section of a manuscript: selection and description of participants, technical information and statistical methods in such detail to allow other investigators to replicate the study exactly. Similarly, specific instructions are provided on the types of references to be used and the styling and formatting of references, tables, figures, and abbreviations. For further details, the reader is directed to Reference #1.

What do we know about reviews and reviewers? Data are contradictory.

1993: Criteria for good peer reviewers2 (strong evidence)

1998: Criteria for good peer reviewers3 (weak evidence)

Blind review (also known as 'masked review') is the situation when the identities of authors and reviewers are not known to one other. Most journals adopt this. Open peer review is when the identities are known. Two randomized controlled studies4,5 revealed that blinding did not affect the quality of the reviews for high profile medical journals. Another study found that the open review system also did not affect the quality of the review.6

|

NOTE: Basic criteria for reviewing can be applied for all types of manuscripts, regardless of the discipline in which the research is grounded. However, as a reviewer, one needs to be aware of the wide variations among journals for requirements and procedures for reviews. |

As a reviewer, it is not common to receive any direct feedback on your review work. Although there has been effort to develop a validated instrument to evaluate a reviewer's performance6, all journals do not routinely use this instrument to evaluate reviewers' work. Most journals will share with the reviewer the final decisions made about the manuscript and comments made by the other reviewers of the same manuscript. This process can provide insights into the quality of one's own review. Although nonspecific, perhaps the best evidence of the value of one's reviewing is a repeat invitation from the journal editor to continue reviewing for the journal.

|

NOTE: Acceptance criteria are different from review criteria. Acceptance criteria depend on the mission of the journal and standards set by the journal's editorial board. |

|

Remember your roles: a reviewer advises the editor and teaches the author. |

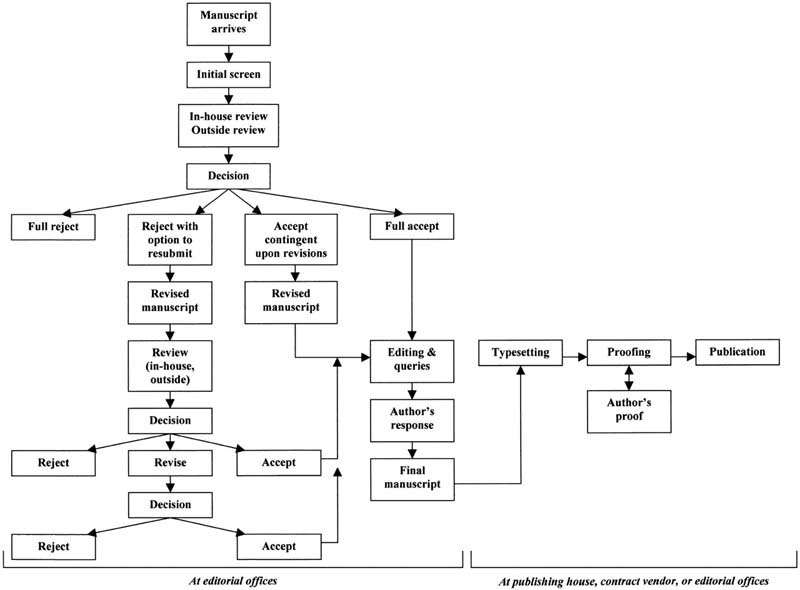

The life of a manuscript flows as follows:

Shea JA; Caelleigh AS; Pangaro L; Steinecke A. Review Process. Academic Medicine. September 2001, 76 (9), pp 911-914. Used with publisher's permission.

FOR REFLECTION

After studying the Life of a Manuscript diagram above, what is most surprising to you about the review process? |

There are at least three methods by which journals use reviewers.

Factors considered: Content expertise, clarity of writing, balanced judgment, responsiveness to the needs of the journal

Mechanisms to identify reviewers:

Often the same reviewers are used for reviewing the revised manuscript to see if the constructive suggestions have been considered by the authors and the paper improved as a result of the feedback.

For each section of the article, the reviewer is asked specific questions with dichotomous or other rating scales. Most require written comments.

The reviewer is then asked to provide a final disposition: accept/ accept with revision/ reject with resubmission option/ reject. Usually the format has a section for constructive suggestions to authors and a separate section for confidential comments to the editor.

This example comes from the journal Medical Education.

|

METHODS

|

|

|

Are these clearly explained? |

Y/N |

|

Are the methods appropriate? |

Y/N |

|

Is the sample size accurate? |

Y/N |

|

Is the sample size representative? |

Y/N |

|

Are the subjects fully described? |

Y/N |

|

Is the statistical method appropriate? |

Y/N |

Another example for open-ended questions comes from Academic Medicine.

|

Explain why the research design and analysis of the data is or is not appropriate for the research question. |

| Given the topic and research question, who in the academic medicine community would be interested in reading this paper? Who (if anyone) should read this paper?

|

|

NOTE: Final decision for publication rests with the editor. The reviewers advise but do not have a vote. |

We will now begin using the Review Criteria for Research Manuscripts, from the Group of Educational Affairs of the Association of American Medical Colleges. In this section, we will consider the 15 reviewing criteria for three areas: Introduction, Review of Literature, Relevance.

Introduction: Look for evidence that the author has thought through the problem and has generated a testable hypothesis. The Introduction moves the reader from what is currently known to what needs to be known and lays the groundwork for what is to follow.

Statement of Problem (or Gap): This section should allow the reader to anticipate the goal(s) of the study.

Conceptual Framework: There should be a clear statement that this work builds on the work of others.

Research Question: A specific research question or goal for the work is usually stated at the end of the introduction. Is it clear? Are the research variables identified?

The literature review helps with:

The literature review provides a logical explanation for why the study was conducted in a certain manner. It may be appropriate to reference work from which the current methods were derived, especially if the current work is designed to test new, or revised, methods.

The author should describe how the background literature search was conducted, especially indicating what databases were searched. References should be mostly from primary sources (those written by persons who did the work), although sometimes it is appropriate to also cite general sources (e.g., authoritative text book) and secondary sources (written by those who comment on or describe previous work). One type of secondary source, the systematic review, is often acceptable and desirable, especially if primary sources are not available. If the literature search is comprehensive, controversies may be identified. The authors may want to highlight these issues to support relevance for the current work. Discussion of these issues may arise again in the Discussion section of the manuscript.

For manuscripts of quantitative work, the literature review establishes the conceptual framework (the work of others) and arrives at a theory driven hypothesis. The literature review is generally placed within the introduction of the manuscript.

For manuscripts of qualitative studies, the literature review is often woven into all phases of the study. Theory building hypotheses evolve as data are collected, transcribed and analyzed.

Will this research affect what the readers will do in their daily work? Is there a practical application or translation of this work? Would a majority of the readers of this journal find the article worth reading?

In this section, we will consider the 24 reviewing criteria for four areas: Research Design; Instrumentation, Data Collection and Quality Control; Population and Sample; and Data Analysis and Statistics.

16. The research design is defined and clearly described and is sufficiently detailed to permit the study to be replicated 17. The design is appropriate for the research question.

18. The design has internal validity; potential confounding variables or biases are addressed.

19. The design has external validity, including subjects, settings and conditions.

20. The design allows for unexpected outcomes or events to occur.

21. The design and conduct of the study are plausible.

Research designs vary, including fully controlled experimental studies and purely observational studies. Sometimes more than one method is used in a study.

The primary tasks for the reviewer are:

22. The development and content of the instrument are sufficiently described or referenced and are sufficiently detailed to permit the study to be replicated

23. The measurement instrument is appropriate given the study's variables; the scoring method is clearly defined

24. The psychometric properties and procedures are clearly presented and appropriate

25. The data set is sufficiently described or referenced

26. Observers or raters were sufficiently trained

27. Data quality control is described and adequate

Decisions about data gathering and data scoring must be clear and logical to the reviewer.

28. The population is clearly defined, for both subjects (study participants) and stimulus cases (i.e., those selected to include in a teaching intervention), and is sufficiently described to permit the study to be replicated

29. The sampling procedures are sufficiently described

30. Subject samples are appropriate to the research question

31. Stimulus samples are appropriate to the research question

32. Selection bias is addressed

|

NOTE: This section is purely about the Methods, not the Results. |

33. Data analysis procedures are sufficiently described and are sufficiently detailed to permit the study to be replicated

34. Data analysis procedures conform to the research design; hypotheses, models or theory drives the data analysis

35. The assumptions underlying the use of statistics are fulfilled by the data, such as measurement properties of the data and normality of the distributions

36. Statistical tests are appropriate

37. If statistical analysis involves multiple tests or comparisons, proper adjustment of significance level for chance outcomes was applied

38. Power issues were considered in statistical studies with small sample sizes

39. In qualitative research that relies on words instead of numbers, basic requirement of data reliability, validity, trustworthiness, and absence of bias were fulfilled

Research design dictates what statistical analysis should be used to analyze the data. Here are points to consider:

FOR REFLECTION

After studying this section on Methods, consider if any of these issues have arisen for you when writing your own manuscripts. If so, how were the issues resolved?

|

In this section, we will consider the nine reviewing criteria for two areas: Reporting of Statistical Analyses and Presentation of Results.

40. The assumptions underlying the use of statistics are considered, given the data collected

41. The statistics are reported correctly and appropriately

42. The number of analyses is appropriate

43. Measures of functional significance, such as effect size or proportion of variance accounted for, accompany hypothesis -testing analysis

|

NOTE: As a reviewer, not understanding the statistical analysis used in the work is not necessarily reason for recusing yourself from the review; but in such a case, you should alert the editor that you have no expertise in this analysis. |

Try to determine if the data satisfy the assumptions necessary for use of the statistical test(s) used. Sometimes the planned analysis may not be feasible after the data are collected (e.g., a planned correlation between two variables cannot be performed because the range of data is very tight; or a t-test was planned to compare the means of two groups, but the results have a bimodal rather than a normal distribution, so the means and standard deviations may not meaningfully describe the data. In the Results section, are statistical analyses reported that are not described in the Methods section? Expansion or addition of new analyses could be inappropriate if done without forethought and careful consideration. An uncontrolled proliferation of analyses or new analyses without adequate explanation is a red flag to the reviewer.

Statistical significance may not mean practical significance. A common situation in which a statistically significant finding may lack clinical significance may occur in a study where the sample size (n) is very large. Small differences between groups may achieve statistical significance but still not be meaningful. Inferential statistical tests only tell us the probability that chance alone produced the results. However they do not reveal the strength of the association among research variables (e.g. effect size). Did the authors attempt to report what proportion of the variance can be explained or accounted by the specific independent variable? Common indices of explained variations are eta 2 in ANOVA and r2 in correlational analyses.

If the independent variable does not account for a reasonable proportion of the variance, the study may not be worthy of publication. Although the result may be statistically significant, it is not caused by the variable tested and therefore may not be interesting to the audience.

44. Results are organized in a way that is easy to understand

45. Results are presented effectively; the results are contextualized

46. Results are complete

47. The amount of data presented is sufficient and appropriate

48. Tables, graphs or figures are used judiciously and agree with the text

The results of the study, and their relationship to the study question and discussion points, must be clear to the reader. Organization of the Results section ideally mirrors organization of the research questions in the introduction of the paper. When several research questions are addressed, the results may be best presented in a series of subsections, each of which addresses one question. This allows the reader to see if each research question has been answered appropriately and completely.

Did the authors critically select which data to present and carefully reflect on how best to present the data?

For qualitative research, the Results section may be organized by themes or by the method of collection of data.

Context of the study must be clearly reported in order to provide a framework for that data, such that reader can judge if the subsequent interpretation reflects the context accurately.

For quantitative data, the balance between descriptive statistics and inferential statistics must be maintained.

Narrative should be used to describe the key results clearly. Tables and graphs should be supplementary or supportive, not the sole presentation of the results. The text must be consistent with the data in the tables and/or figures.

Extrapolation of the results to the research question and discussion of implications of the work belong in the Discussion section of the paper, not in the Results section.

FOR REFLECTION

What challenges do you have for writing the Results section of a paper? What challenges do you anticipate for reviewing the Results section? Consider your own experiences of trying to include all your results appropriately in tables or graphs? What have you learned from these experiences? Consider how you would critique the data presentation below. This graph shows productivity in a lab after implementation of a faculty development program in research. Are the data sufficient? Too much? Not enough?

Advice: When reviewing the tables, figures and graphs in the Results section of a manuscript, if pertinent, offer suggestions on how the data can be presented in a concise and effective way to deliver the major point of an article to the average reader. In such presentations, there is always a tension between the comprehensiveness of the data presented versus the effectiveness of the message.

|

In this section, we will discuss the 18 reviewing criteria for interpretation of the results as presented in the Discussion (or Conclusion) section of a manuscript and will consider issues related to the title, authorship, and abstract.

49. The conclusions are clearly stated; key points stand out

50. The conclusions follow from the design, methods, and results; justification of conclusions is well articulated

51. Interpretations of the results are appropriate, conclusions are accurate ( not misleading)

52. The study limitations are discussed

53. Alternative interpretations of the findings are considered

54. Statistical differences are distinguished from meaningful differences

55. Personal perspectives or values related to the interpretation are discussed

56. Practical significance or theoretical implications are discussed; guidance for future studies is offered

Reviewers should be convinced that the interpretation of the results is justified. In addition, given the limitations and architecture of the study, reviewers should judge the generalizability and practical significance of the study.

Reviewers must evaluate whether each research hypothesis is refuted or confirmed and whether each conflicts with or aligns with previous research.

Qualitative approaches: did the author convince the reader that data are trustworthy? Are the data credible (internal validity) and transferable (external validity)? Techniques for enhancing data credibility include triangulation, member checking and peer debriefing. Have multiple data sources (triangulation) been used? Have interpretations been "tested" with those from whom the data were collected during interviews (member checking)? Have disinterested peers analyzed the data and confirmed or expanded the researcher's conclusions (peer debriefing)?

57. The title is clear and informative

58. The title is representative of the content and breadth of the study ( not misleading)

59. The title captures the importance of the study and the attention of the reader

Reviewing the title and abstract are the beginning and the end of the review process. The title is the shortest abstract. It must be indicative (describing the nature of the study) andinformative (presenting the message derived from the study results).

Example of an indicative and informative title is "A Survey of Academic Advancement in Divisions of General Internal Medicine: Slower Rate and More Barriers for Women." Contrast this with the title "Academic Advancement in Women" where neither the nature of the study not the key message is evident in the title.

60. The number of authors appears to be appropriate given the study

Reviewers are not responsible for setting criteria for authorship. We discuss authorship ethics in a subsequent section.

There are internationally approved criteria for authorship. The reviewer should appraise whether the number of authors are appropriate for the type of study conducted. Reports of multi-institutional projects or collaborative topic based national task force activities are likely to have several authors. Often in such cases, the lead authors are listed separately from those that were involved in the task force or committee.

61. The abstract is complete (thorough), essential details are presented

62. The results in the abstract are presented in sufficient and specific detail

63. The conclusions in the abstract are justified by the information in the abstract and the text

64. There are no inconsistencies in detail between the abstract and the text

65. All of the information in the abstract is present in the text

66. The abstract overall is congruent with the text; the abstract gives the same impression as the text

Typically, a journal editor will request these sections for an abstract of an original study:

An abstract for a review article should contain the following:

Three common deficits in abstracts are these:

67. The text is well written and easy to follow

68. The vocabulary is appropriate

69. The content is complete and fully congruent

70. The manuscript is well organized

71. The data reported are accurate (the numbers add up) and appropriate; tables and figures are used effectively and agree with the text

72. Reference citations are complete and accurate

Have the authors clearly and effectively presented their data? Have they interpreted their results accurately? Have they successfully communicated the key patterns in information to the reader?

Has the manuscript been organized according to the Uniform Requirements guidelines1 using the IMRAD format (if applicable)? Is there a logical progression in the thought process?

Do the graphs and figures present information efficiently and aid in the communication of complex ideas?

How well has the author matched the level of communication to the complexity of the topic discussed?

Are there adequate references to key original articles on the topic?

73. No plagiarism is detected

74. Ideas and materials of others are correctly attributed

75. Prior publication by the author(s) of substantial portions of the data or study is appropriately acknowledged

76. No conflict of interest is apparent

77. The text explicitly describes approval by an institutional review board for studies directly involving human subjects or data about them

This section includes points of etiquette for reviewers. Although strictly these are not criteria for review of the manuscript, they are extremely important to maintain ethical and professional standards among reviewers. When a reviewer agrees to review a manuscript, in addition to meeting the deadlines, s/he accepts responsibilities of confidentiality, avoidance of conflict of interest as well as ensuring a collegial and constructive approach to the review process.

|

NOTE: A manuscript under review is the sole property of the author, so it should be destroyed after your review. It can be shared with permission from the editor if content expertise is needed by the reviewer. |

|

REFERENCE: Task Force of Academic Medicine and the GEA-RIME Committee. Checklist of Review Criteria for Research Manuscripts. Academic Medicine. September 2001, 78 (9), 920-921. |

1. The introduction builds a logical case and context for the problem statement

2. The problem statement is clear and well articulated

3. The conceptual (theoretical) framework is explicit and justified

4. The research question (research hypothesis where applicable) is clear, concise and complete

5. The variables being investigated are clearly identified and presented

6. The literature review is up to date

7. The number of references is appropriate and the selection is judicious

8. The review of the literature is well integrated

9. The references are mainly primary sources

10. Ideas are acknowledged appropriately (scholarly attribution) and accurately

11. The literature is analyzed and critically appraised

12. The study is relevant to the mission of the journal or its audience

13. The study addresses important problems; the study is worth doing

14. The study adds to the literature already available on the subject

15. The study has generalizability because of the selection of subjects, setting and educational intervention or materials

16. The research design is defined and clearly described and is sufficiently detailed to permit the study to be replicated

17. The design is appropriate (optimal) for the research question

18. The design has internal validity; potential confounding variables or biases are addressed

19. The design has external validity, including subjects, settings and conditions

20. The design allows for unexpected outcomes or events to occur

21. The design and conduct of the study are plausible

22. The development and content of the instrument are sufficiently described or referenced and are sufficiently detailed to permit the study to be replicated

23. The measurement instrument is appropriate given the study's variables; the scoring method is clearly defined 24. The psychometric properties and procedures are clearly presented and appropriate

25. The data set is sufficiently described or referenced

26. Observers or raters were sufficiently trained

27. Data quality control is described and adequate

28. The population is clearly defined, for both subjects (participants) and stimulus( intervention), and is sufficiently described to permit the study to be replicated

29. The sampling procedures are sufficiently described

30. Subject samples are appropriate to the research question

31. Stimulus samples are appropriate to the research question

32. Selection bias is addressed

33. Data analysis procedures are sufficiently described and are sufficiently detailed to permit the study to be replicate

34. Data analysis procedures conform to the research design; hypotheses, models or theory drives the data analysis

35. The assumptions underlying the use of statistics are fulfilled by the data, such as measurement properties of the data and normality of the distributions

36. Statistical tests are appropriate (optimal)

37. If statistical analysis involves multiple tests or comparisons, proper adjustment of significance level for chance outcomes was applied

38. Power issues were considered in statistical studies with small sample sizes

39. In qualitative research that relies on words instead of numbers, basic requirement of data reliability, validity, trustworthiness, and absence of bias were fulfilled

40. The assumptions underlying the use of statistics are considered, given the data collected

41. The statistics are reported correctly and appropriately

42. The number of analyses is appropriate

43. Measures of functional significance, such as effect size or proportion of variance accounted for, accompany hypothesis - testing analysis

44. Results are organized in a way that is easy to understand

45. Results are presented effectively; the results are contextualized

46. Results are complete

47. The amount of data presented is sufficient and appropriate

48. Tables, graphs or figures are used judiciously and agree with the text

49. The conclusions are clearly stated; key points stand out

50. The conclusions follow from the design, methods, and results; justification of conclusions is well articulated

51. Interpretations of the results are appropriate, conclusions are accurate ( not misleading)

52. The study limitations are discussed

53. Alternative interpretations of the findings are considered

54. Statistical differences are distinguished from meaningful differences

55. Personal perspectives or values related to the interpretation are discussed

56. Practical significance or theoretical implications are discussed; guidance for future studies is offered

57. The title is clear and informative

58. The title is representative of the content and breadth of the study ( not misleading)

59. The title captures the importance of the study and the attention of the reader

60. The number of authors appears to be appropriate given the study

61. The abstract is complete (thorough), essential details are presented

62. The results in the abstract are presented in sufficient and specific detail

63. The conclusions in the abstract are justified by the information in the abstract and the text

64. There are no inconsistencies in detail between the abstract and the text

65. All of the information in the abstract is present in the text

66. The abstract overall is congruent with the text; the abstract gives the same impression as the text

67. The text is well written and easy to follow

68. The vocabulary is appropriate

69. The content is complete and fully congruent

70. The manuscript is well organized

71. The data reported are accurate (the numbers add up) and appropriate; tables and figures are used effectively and agree with the text

72. Reference citations are complete and accurate

73. There are no instances of plagiarism

74. Ideas and materials of others are correctly attributed

75. Prior publication by the author(s) of substantial portions of the data or study is appropriately acknowledged

76. There is no apparent conflict of interest

77. There is an explicit statement of approval by an institutional review board for studies directly involving human subjects or data about them

These criteria for authorship were developed by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. All authors should meet criteria, and all who meet criteria should become authors.

Contributions not warranting authorship include:

Types of authorship abuse, as discussed by Strange8, include:

FOR REFLECTION

Reflect on reasons why academicians may falter on authorship ethics. With which of these forms of unethical authorship were you familiar? Consider strategies to avoid authorship disputes among collaborators. |

1. Uniform Requirements for Manuscripts Submitted to Biomedical Journals: Writing and Editing for Biomedical Publication. Available from http://www.icmje.org/index.html#top.

2. Evans AT, McNutt RA, Fletcher SW, Fletcher RH. The characteristics of peer reviewers who produce good quality reviews. J Gen Intern Med. 1993;8: 422-8

3. Black N, van Rooyen, Godlee F, Smith R, Evans S. What makes a good reviewer and a good review for a general medical journal? JAMA 1998;280: 23

4. van Rooyen S, GodleeF, Evans S., et al. Effect of blinding and unmasking on the quality of the peer review. JAMA.1994;272:147-9.

5. Justice AC, Cho MK, Winker MA, Berlin JA, Rennie D. Peer investigators:Does masking author identity improve peer review quality? A randomized control trial. JAMA. 1998;280:240-2

6. Fruer ID, Becker GJ, Picus D, Ramirez E, Darcy MD, Hicks ME. Evaluating peer reviews: pilot testing of a grading instrument. JAMA.1994;272:117-9.

7. Fiske DW, Fogg L. But the reviewers are making different criticisms of my paper! Diversity and uniqueness in reviewer comments. Am Psychologist. 1990;45: 591-8.

8. Strange K. Authorship: why not just toss a coin? Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2008 Sept.; 295(3):C567-575.

Bordage G, Caelleigh AS, Steinecke A, Bland CJ, Crandall SJ, McGaghie WC, Pangaro LN, Penn G, Regehr G, Shea JA. Review Criteria for Research Manuscripts. Joint Task Force of Academic Medicine and the GEA-RIME committee. Academic Medicine 76(9) Sep 2001.

This is the primary reference for this module. It is a series of 28 documents, presenting a thorough description of the review process, the review criteria, with samples of review sheets from journals included in the appendix. It is especially useful to evaluate medical education research articles.

Bryne, DW. Common Reasons for Rejecting Manuscripts at Medical Journals: A Survey of Editors and Peer Reviewers. Science Editor. 2000: Vol. 23 (2), pp 39-44.

This article reports the results of a survey among editors and peer reviewers discussing the common reasons why manuscripts are rejected and the areas of deficiencies frequently found in each section of a manuscript.

Equator-Network. Enhancing the Quality and Transparency of Health Research. http://www.equator-network.org/home/

This site has excellent resources for authors and reviewers, including the following: Guidelines for reporting qualitative research; Guidelines for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analysis; Research ethics, publication ethics and good practice guidelines; Instructions to Authors; Common Omissions and Errors in Published Research, Guidance for peer reviewers; Resources for editors and peer reviewers

ICMJE. www.icmje.org/table1.pdf

Listing of the 20 criteria for a fully registered clinical trial

International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICJME), Uniform Requirements for Manuscripts, http://content.nejm.org/cgi/content/full/336/4/309

This site lists the Uniform Requirements for Manuscripts submitted to biomedical journals published by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors ICJME. A must read for all potential authors.

Oxman AD, Sackett DL, Guyatt GH. Users Guide to the Medical Literature JAMA 1993. 270(17) 2093-5. De Angelis C, Drazen JM, Frizelle FA, Haug C, Hoey J, Horton R, et al. Clinical trial registration: a statement from the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:477-8. Epub 2004 Sep 8.

Information on appropriate and full registration of clinical trials from ICMJE.

Oxman AD. Systematic Reviews: Check lists for review articles. BMJ 1994;309. 648-651.

Discussion of the types of biases that can affect systematic reviews and the various roles of the reviewers and editors in validating the manuscript

Reed DA, Cook DA, Beckman TJ, Levine RB, Kern DE, Wright SM. Association between funding and quality of published medical education Research. JAMA 2007; 298(9): 1002-1009.

This article describes the MERSQI, a ten item tool to evaluate the quality of educational research

This module was developed by Latha Chandran MD, MPH and Virginia Niebuhr, PhD, using as their primary source, and with permission from the editor, a document published by a task force of the Group of Educational Affairs of the Association of American Medical Colleges.

Bordage G, Caelleigh AS, Steinecke A, Bland CJ, Crandall SJ, McGaghie WC, Pangaro LN, Penn G, Regehr G, Shea JA. Review Criteria for Research Manuscripts.

Joint Task Force of Academic Medicine and the GEA-RIME committee. Academic Medicine 76(9) Sept 2001.

The module was first developed for use with an intersession activity of the Academic Pediatric Association's Educational Scholars Program (APA-ESP).

|

|

Dr. Chandran is Professor in the Department of Pediatrics, Vice Dean for Undergraduate Medical Education, and general pediatrician at Stony Brook University School of Medicine. She is the Co-Director of the Academic Pediatric Association's Educational Scholars Program. She is on the editorial board of Pediatrics and has served on the editorial board of Pediatrics in Review. Latha.Chandran@stonybrookmedicine.edu.

|

|

|

Dr. Niebuhr is Professor in the Department of Pediatrics, and a Pediatric Psychologist, at the University of Texas Medical Branch. She is a faculty member for the Academic Pediatric Association's Educational Scholars Program. Much of her work focuses on faculty development in the area of educational technology. vniebuhr@utmb.edu

|

This module was created using Softchalk, V6.06.05